People also search for. Morris Engel 4.10 Rating details 134 ratings 14 reviews A concise, easy-to-read introduction to informal logic, With Good Reason offers both comprehensive coverage of informal fallacies and an abundance of engaging examples of both well-conceived and faulty arguments.

- With Good Reason By Morris Engel Sixth Edition

- See Full List On Openlibrary.org

- S. Morris Engel With Good Reason 6th Edition

- With Good Reason: An Introduction To Informal Fallacies - S ...

- Cached

With good reason by S. Morris Engel, 1986, St. Martin's Press edition, in English - 3rd ed. Logic terms pages 301-306 in With Good Reason by S.Morris Engel. Learn with flashcards, games, and more — for free.

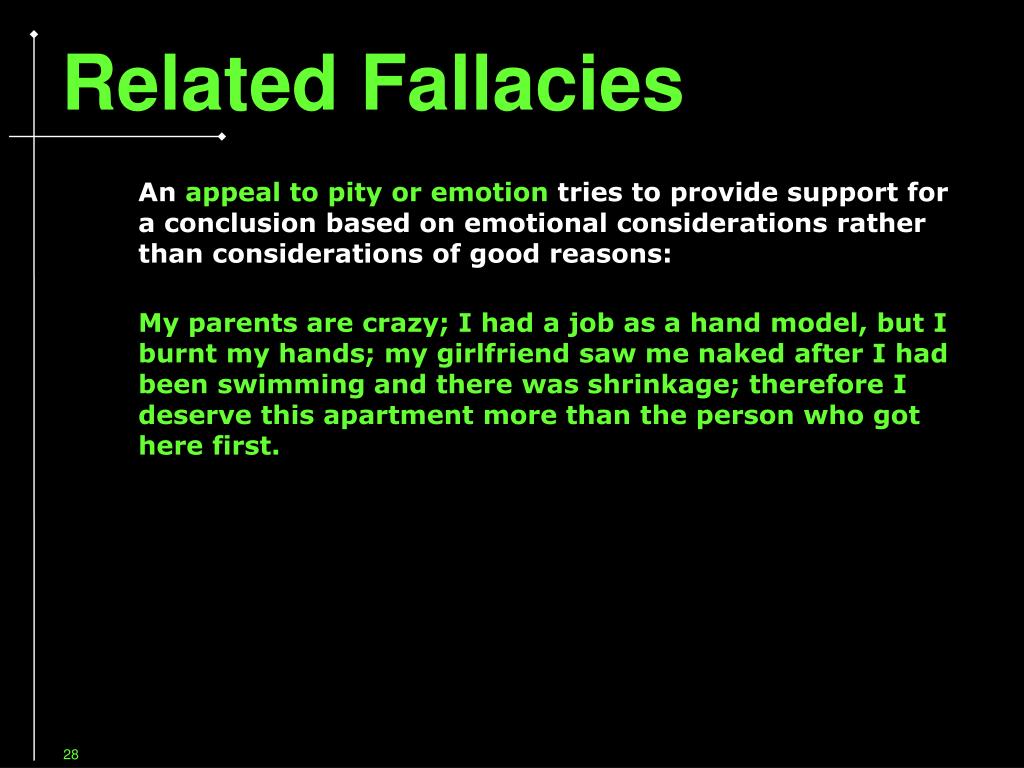

A concise, easy-to-read introduction to informal logic, With Good Reason offers both comprehensive coverage of informal fallacies and an abundance of engaging examples of both well-conceived and faulty arguments. A long-time favorite of both students and instructors, the text continues in its sixth edition to provide an abundance of exercises that help students identify, c A concise, easy-to-read introduction to informal logic, With Good Reason offers both comprehensive coverage of informal fallacies and an abundance of engaging examples of both well-conceived and faulty arguments. A long-time favorite of both students and instructors, the text continues in its sixth edition to provide an abundance of exercises that help students identify, correct, and avoid common errors in argumentation.

PDF With Good Reason An Introduction To Informal Fallacies Available link of PDF With Good Reason An. Introduction to Informal Fallacies S Morris Engel Books.

If you are searching for a ebook With Good Reason: An Introduction to Informal Fallacies by S. Morris Engel in pdf form, in that case you come on to the correct website. PDF Download personal. Book Review: With Good Reason. Morris Engel has provided an excellent work on informal fallacies. With Good Reason: An Introduction To Informal Fallacies By S. Morris Engel Do you enjoy reading or your need a lot of educational materials for your.

This book is best for the examples and exercises. My favorite (from a discussion of Amphiboly): 'Dog for sale. Will eat anything. Especially fond of children.'

With Good Reason By Morris Engel Sixth Edition

Main weaknesses were: 1. Organization: In general, Irving Copi's presentation is better organized. For example, Engel divides disagreements into genuine and linguistic disagreements. Copi very helpfully adds a third category: apparently linguistic disagreements.

Engel's oddly subsumes this category under 'linguistic disagreements.' Many in This book is best for the examples and exercises.

My favorite (from a discussion of Amphiboly): 'Dog for sale. Will eat anything. Especially fond of children.' Main weaknesses were: 1. Organization: In general, Irving Copi's presentation is better organized.

For example, Engel divides disagreements into genuine and linguistic disagreements. Copi very helpfully adds a third category: apparently linguistic disagreements. Engel's oddly subsumes this category under 'linguistic disagreements.'

Many introductory logic books, Engel's included, give the impression that arguments are conducted merely by flagging down fallacies. I call amphiboly! Caught you using the Fallacy of Accent! You just asked a Complex Question!

This may be how exercises in logic books work. But in the real world you don't defeat arguments by announcing their fallaciousness. You have to argue for their fallaciousness, like you have to argue for everything else. A nice two-paragraph warning here would have been helpful. I could have done without the cheap shots at Christianity.

'I am the way, the truth, and the life' is not an example of fallacious personification. It is a figure of speech and a rather striking one at that. If you can't get this, then, well, you probably spend too much time reading boring logic books and need to get out more.

See Full List On Openlibrary.org

And that last sentence isn't an example of poisoning the well. Well worth reading. Even more than reading, well worth studying.

I can't help but wonder what the author thinks about public discourse today. Perhaps never in history have informal fallacies been more commonplace. Everywhere one turns, from nightly news to magazines to social media, one finds innumerable examples of what the author warns us about. On the other hand, it is possible (and even likely?) that some may utilize this book precisely to learn the art of informal fallacies for the purpose Well worth reading. Even more than reading, well worth studying. Vista Market El Paso Tx Hours. I can't help but wonder what the author thinks about public discourse today.

S. Morris Engel With Good Reason 6th Edition

With Good Reason: An Introduction To Informal Fallacies - S ...

Perhaps never in history have informal fallacies been more commonplace. Everywhere one turns, from nightly news to magazines to social media, one finds innumerable examples of what the author warns us about. On the other hand, it is possible (and even likely?) that some may utilize this book precisely to learn the art of informal fallacies for the purpose of persuasion. At each of the many examples given in the book, I would find myself thinking of corresponding examples in mainstream media from just the past few months. (I would love to cite examples, but I'm afraid that would be considered a microaggression!) I'm concerned that too many people have lost the capacity to think rationally. In a better world, we would all agree to read this book, and then agree to call out informal fallacies wherever they are perpetrated on us. We should not have to put up with 'fake news.'

Cached

- William Lane Craig, The Only Wise God: The Compatibility of Divine Foreknowledge and Human Freedom (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1987),Google Scholar

- See M. B. Ahern, The Problem of Evil (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, Ltd., 1971), p. ix.Google Scholar

- See Alvin Plantinga’s, Does God Have a Nature? (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 1980).Google Scholar

- For a helpful discussion of this doctrine see Plantinga’s Does God Have a Nature? pp. 95–110.Google Scholar

- For a helpful discussion of this doctrine see Plantinga’s Does God Have a Nature? pp. 95–110. Cf. P. T. Geach, Providence and Evil (Cambridge University Press, 1977), p. 8f, andGoogle Scholar

- Anthony Kenny, The God of the Philosophers (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979), pp. 91f.Google Scholar

- W. V. Quine, Methods of Logic (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc., 1950), p. 3.Google Scholar

- Alvin Plantinga, God and Other Minds (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1967), p. 171. In this context, Plantinga addresses the ‘omnipotence paradox’ introduced by J. L. Mackie in ‘Evil and Omnipotence,’ p. 210. The paradox is started by the question, Can God make things he cannot then control? If we say ‘Yes,’ then once he has made them he is not omnipotent. If we say ‘No,’ then we are admitting that there are things that God cannot do. Richard La Croix argues that it is a concept that is impossible to define, in ‘The Impossibility of Defining Omnipotence,’ Philosophical Studies, Vol. 32 (1977), pp. 181–190.Google Scholar

- See S. Morris Engel, With Good Reason (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1976), p. 145.Google Scholar

- Richard La Croix, ‘The Impossibility of Defining Omnipotence,’ Philosophical Studies, Vol. 32 (1977), p. 183.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

- Richard Swinburne, The Coherence of Theism (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977), p. 162.Google Scholar

- Here, I am assuming that the omniscient being is within time even though he might be eternal. A very different rendering would be required if the theist were to hold that God is omniscient and atemporally eternal. See Eleanore Stump’s and Norman Kretzmann’s article, ‘Eternity’, The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 78, No. 8 (August, 1981), pp. 429–458.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

- This particular locution is attributed to Elizabeth Anscombe by Anthony Kenny, The God of the Philosophers (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979), p. 48, n. 1. The counterexample is supplied by Norman Kretzmann.Google Scholar

- J. R. Lucas, The Freedom of the Will (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1970), p. 71.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

- Reformed theologians, John Murray and Ned B. Stonehouse, and apologist Cornelius Van Til argued that there is such a radical difference, challenging Gordon H. Clark on the matter of God’s incomprehensibility at his ordination examination. See Fred H. Klooster, The Incomprehensibility of God in the Orthodox Presbyterian Conflict (Franeker: T. Wever, 1951).Google Scholar

- Cf., John H. Frame, The Doctrine of the Knowledge of God (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1987), pp. 21–40.Google Scholar

- George Mavrodes, ‘How Does God Know the Things He Knows,’ Divine and Human Action, Thomas Morris (ed.), Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1989.Google Scholar

- René Descartes held to an absolute omnipotence doctrine such that God is somehow supralogical and hence can, ‘if he wants,’ nullify or set aside the canons of logic and make true a contradictory proposition or do something that would be contradictory for him to do. Actually, his position was ambiguous. His writings may be interpreted as supporting either universal or limited possibilism. The former is the view that Descartes’ ‘eternal truths,’ e.g., the truths of logic, mathematics, etc., are not necessary truths. The latter position by contrast affirms that eternal truths are necessary, but they owe their necessity to divine decree. See Alvin Plantinga’s, Does God Have a Nature? (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 1980), pp. 95–110.Google Scholar

- Nelson Pike, ‘Divine Foreknowledge, Human Freedom and Possible Worlds,’ The Philosophical Review, Vol. 86, No. 2 (April, 1977), p. 209. In Divine Nature and Human Language (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989), William Alston argues that God does not have beliefs, pp. 178–193CrossRefGoogle Scholar

- Linda Trinhaus Zagzebski, The Dilemma of Freedom and Foreknowledge (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 142.Google Scholar

- William Lycan, ‘The Trouble with Possible Worlds,’ The Possible and the Actual, ed., Michael J. Loux (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1979), p. 287.Google Scholar

- See Peter van Inwagen’s Material Beings (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991), for an interesting account of such things as trees, clouds, and puppy dogs’ tails.Google Scholar

- Nelson Pike, God and Timelessness (New York: Schocken, 1970), pp. 121–129, cf., Zagzebski’s The Dilemma of Freedom and Foreknowledge, pp. 43f., for other criticisms of this view of God’s eternity.Google Scholar

- William Hasker, ‘Response to Thomas Flint,’ Philosophical Studies, 60, (1990), p. 120. See this article for an elegant argument against middle knowledge.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

- J. R. Lucas, The Future (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989), p. 226.Google Scholar

- See Charles Hartshorne, The Divine Relativity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1948), pp. vii, 43, 83, 94. The theist, of course, can benefit from some of Hartshorne’s insights, without buying into process theology.Google Scholar

- Bruce Reichenbach, ‘Evil and a Reformed View of God,’ International Journal for Philosophy of Religion, Vol. 24 (1988), pp. 67–85, particularly pp. 70–74.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

- John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1957), I, 15, 8.Google Scholar

- Alvin Plantinga, The Nature of Necessity, p. 166. Cf. pp. 14f., Peter van Inwagen, An Essay on Freewill (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983).Google Scholar

- George Botterill, ‘Falsification and the Existence of God: A Discussion of Plantinga’s Free Will Defence,’ The Philosophical Quarterly (April, 1977), Vol. 27, No. 107, pp. 114–134.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

- Representing the Western tradition, Henry Mansel and Emil Brunner fall into this camp. Both held to the unknowability of God and so also its corollary the unknowability of his goodness. See Emil Brunner’s God and Man (London: SCM Press, 1936), pp. 59, 60, 76–84.Google Scholar

- Cf. G. Stanley Kane, ‘The Concept of Divine Goodness and the Problem of Evil,’ Religious Studies, Vol. II, No. 1 (March, 1975), 49–71. Kane includes Karl Barth, see Barth’s Church Dogmatics, II. 1, pp. 188,189; II. 2, pp. 631–636 (Edinburgh, T. & T. Clark, 1936). Barth also clearly affirms God’s knowability, see Church Dogmatics II. 2, pp 4f., 147ff., 156f., 158ff.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

- James F. Ross, Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion (London: The Macmillan Company, 1969), p. 167.Google Scholar

- For a more detailed discussion of the concept of analogy see, James F. Ross, ‘Analogy as a Rule of Meaning for Religious Language,’ Inquiries into Medieval Philosophy, James F. Ross (editor), (Westport: Greenwood Publishing Company, 1971), pp. 35–74.Google Scholar

- Frederick Ferré, Language, Logic and God (New York: Harper and Row, 1961), p. 75. The terms neo-orthodox and reformed do not designate two clearly distinct groups, since some neo-orthodox theologians would be comfortable with the designation, ‘reformed.’Google Scholar